Depending on size, species

and age, birds may have between 940 (hummingbird) and 25,216 (swan) feathers.

Each of these feathers is molted and replaced on average every six months.

Feathers on a bird are not evenly distributed. They grow in

distinct tracts or lines called pterylae, inbetween areas of bare skin called

apteria. The apteria help cool the

bird. Apteria vary in size and are

typically covered with contour, or body feathers, that overlap the

apteria. Because of the effects of

water on feathers and ultimately on body temperature, water birds have small

apteria and penguins have almost none.

New feathers emerging on the head of an African grey parrot. (photo: Dawn Trainor Griffard)

As a bird molts a feather,

the new emerging feather pushes up into the base of the older feather,

eventually forcing the older feather out of the follicle (place of feather

growth) altogether. As a new feather grows into place, it is nourished with

blood by a small artery, which allows for its growth.

The growing sheath the new feather,

along with the feather itself, is formed of keratin – just like human fingernails. The growing sheath is semi-sharp and hard enough so it can press through

the epidermis (outer layer of skin).

During a heavier molt, this is the part of the process that makes our

companion birds a little uncomfortable and crabby. It’s probably an annoying

and itchy process!

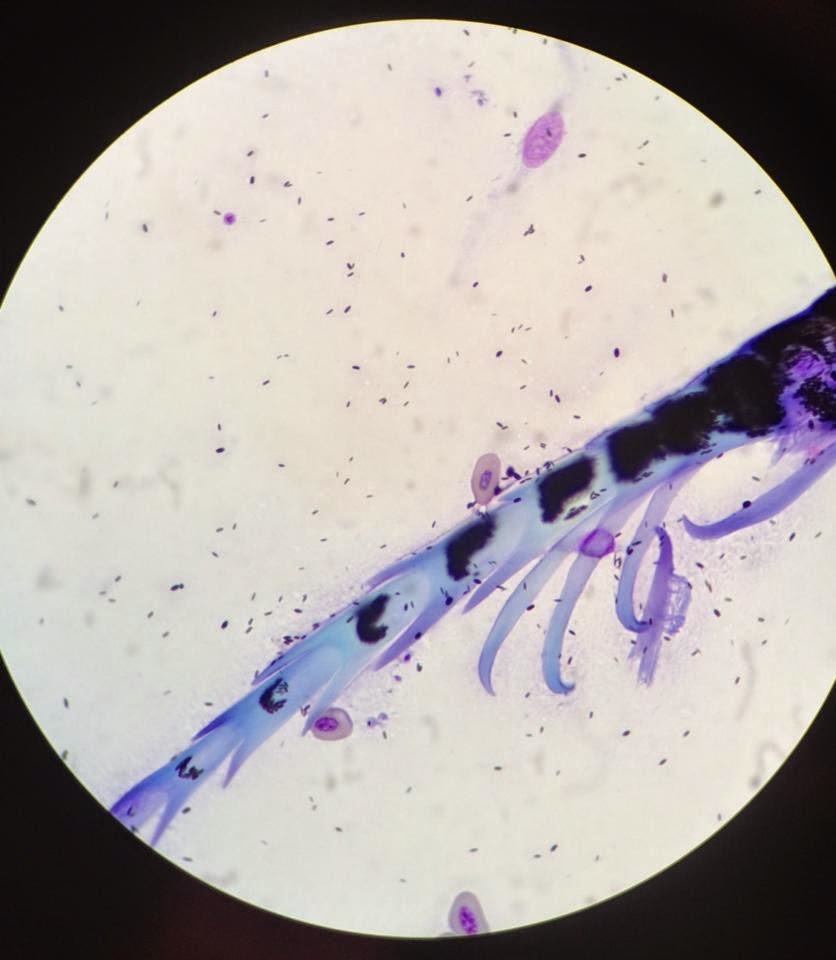

Actively growing primary flight feather with a blood supply (photo: Dawn Trainor Griffard)

Before the new feather

erupts from the growth sheath, it’s referred to

as a “pin” feather until the keratin sheath falls off or is removed, and you

can see the actual feather. As the feather grows the protective

sheath either sloughs off or is preened off by

the bird. When a feather completes its growth, the blood supply to the feather stops.

Problems can arise when a

feather is accidentally damaged during its growth period. If a blood feather is

damaged during its development, it can bleed profusely, endangering the health

of the bird. Birds with actively bleeding blood feathers must be attended to immediately. However, only intervene if the feather

will not stop bleeding. Usually

the broken blood feather bleeds a little, then stops bleeding on its own. Then the body usually stops blood flow

to the feather, the bird preens the broken feather out, and a new feather

starts to grow. It’s most

important to figure out how the bird broke the feather and make sure it doesn’t

happen again.

Microscopic view of the “birth” of a feather (photo: Dawn Trainor Griffard)

If the bleeding will not

stop, the blood feather is either carefully trimmed or completely pulled out –

the latter of which is probably a painful procedure as the feather is often

attached to a bone, so removal must be done expertly and quickly.

If the damage is slight yet

the bleeding won’t stop, you can stop it with

cornstarch and/or direct pressure. However, care must be taken that the feather

does not receive further damage. In

almost all instances the bird would have to be restrained for this procedure,

so letting the bird’s body naturally take care of the broken blood feather is

best.

Through its daily preening,

the growth sheath is removed by the bird itself

or a conspecific – usually the mate. In captivity, the bird’s keeper can often gently

remove those growth sheaths the bird cannot reach (like on the back of the head),

as long as the bird tolerates being touched.

At the World Bird Sanctuary our birds are fed nutritious diets and are monitored very closely to

ensure that the molting process goes smoothly. If we see that one of our birds is having a problem with a bloodfeather

or that a growth sheath is not being shed, we can step in and intervene to

ensure the health and comfort of our birds.

Submitted by Dawn Trainor Griffard, World Bird Sanctuary Naturalist

No comments:

Post a Comment